All The Stuff You Think Matters, Don't Matter

You can never be certain about most things.

But there's one thing you can be certain of: Death.

Legend has it that, after a major military victory, Roman generals would parade through the streets with a slave trailing behind. The sole responsibility of the slave was to continuously whisper into the general’s ear: Respice post te. Hominem te esse memento. Memento mori!

Look behind, the slave would say, remember you are mortal. Remember you will die.

It’s challenging to keep death at the forefront of thought. We’re simply not wired to process life in one linearity. Instead, we think about life as a race—that it's all about what we can achieve, how far we can go, who we beat along the way. But if that is truly the mission, why do people on their deathbeds all say the same thing? I wished I had done more of this. I wished I had focused less on my career and more on my interests and passions. I wished I had spent more time with my spouse. My kids. My loved ones.

What once meant the world finally trickled into nothingness, and regardless of the life that we lived, we all end up at the same point.

Rich, smart, good-looking, successful or not, it doesn’t matter. You will die.

I was lucky to part of a family where academic achievement was not a criteria to be part of the family. Sure, it always a good thing to do well in school, but that's just a bonus. So it seemed pretty normal to my parents that, instead of paving my way into college, I got my diploma and dived straight into the adult's world. It was incredibly helpful that they believed children should have the freedom to direct their lives toward what they felt was right. After all, they were business people—they understood that the real game begins the moment we graduate. Their emphasis was on how well we could make money—by any means necessary (legally of course)—which they knew wasn’t correlated to how far you went in school.

They were hard workers. They never backed down. Disciplined, gritty, determined, always summoning themselves when they were called. Never once did they make us feel bad for enjoying the fruits of our labour, showing us that by doing so, we are respecting ourselves and the efforts of our craft. They exemplified that it was alright to fail, alright to cry, alright to hit the restart button if things aren't working out.

What matters at the end of the day, my mother would say, is that we’re together as a family.

Sure, they were far from perfect—many times I desired more than what I was shown—but they were unwavering in their support, relentless in their love, which, as I reflect upon time and time again, shaped the way I lived my life.

Most of friends who knew about my decision not to pursue further education were surprised, not in a condescending way, but because in where I’m from, earning a bachelors or anything beyond was the socially-acceptable, unquestionable wise path for any young person wanting to make even a small dent in society. Yet, till this day, after working for more than ten years, never once did this lack of a paper become a problem for any business deal or project.

And because of this, I was appalled when I read about about Command Education, a US-based education consultancy that charges clients a whopping $120,000 a year to help their kids get into their dream college. Estimated to be worth $2.9 billion, the industry's business model is to prey on the insecurities of ultra-rich parents by offering a personalised white glove service. It helps their kids to road map their way into their top-choice college. It was even so competitive among the clientele that a parent at Trinity School in Manhattan offered to pay $1.5 million not to work with any other student in his kids’ class. One even paid $10,000 for a 45-minute “download” about the latest trends in college admissions. These parents clearly placed a sky-high emphasis on their children's post-highschool paths, which I suspect was heavily influenced by family reputation and status. Did anyone bother to ask the kids were okay with it? That this is what they want?

Don’t get me wrong. I’m not justifying my lack of a degree as a substitute for my passion (I was qualified but chose not to pursue it). In fact, I think kids should go to college because it’s an enriching experience that deals you more than just an academic hand. But I wonder if college would have prepared me for the reality of being an entrepreneur and the struggles (which nobody warned me about) that come with it.

Would any amount of education have prepared me for a sophisticated world not dictated by any rules?

Here’s what I thought mattered: how well can I communicate the power of my product to a potential customer. In other words, sales. I have this creative programme. It’s line up with the best experiences. The best educators. The best activities. I’m fully convinced that your child or students will be reap a line of benefits that would strengthen their creativity and help them win at life. How do I write/say/present to the best of my abilities? It requires you to come up with all sorts of ways—creative, shrewd, unconventional—to seal the deal.

Bottomline is king, and the upside will determine the longevity of your venture. This is the reality for most people in business.

For most authors, hitting the New York Times Bestseller list is probably the most career goal. When Ryan Holiday’s first book came out, he worked so hard to get the sales numbers up so he could say he was a NYT bestseller. Instead, his efforts could only earn him a Wall Street Journal listing. Turns out, the newfound title had zero impact on the sales of the book or his ability to have a writing career. What mattered, just like most businesses, was whether the sales number was going up and whether he had anything interesting to say. Eventually he did get on the NYT Bestseller list, but nothing changed for him. In the end, he realised only some things were worth his time and effort: ”Writing a book that I’m proud of, saying what I have to say, growing as a writer in doing it, making something that reaches people, that makes a difference in their lives? That’s way more important.”

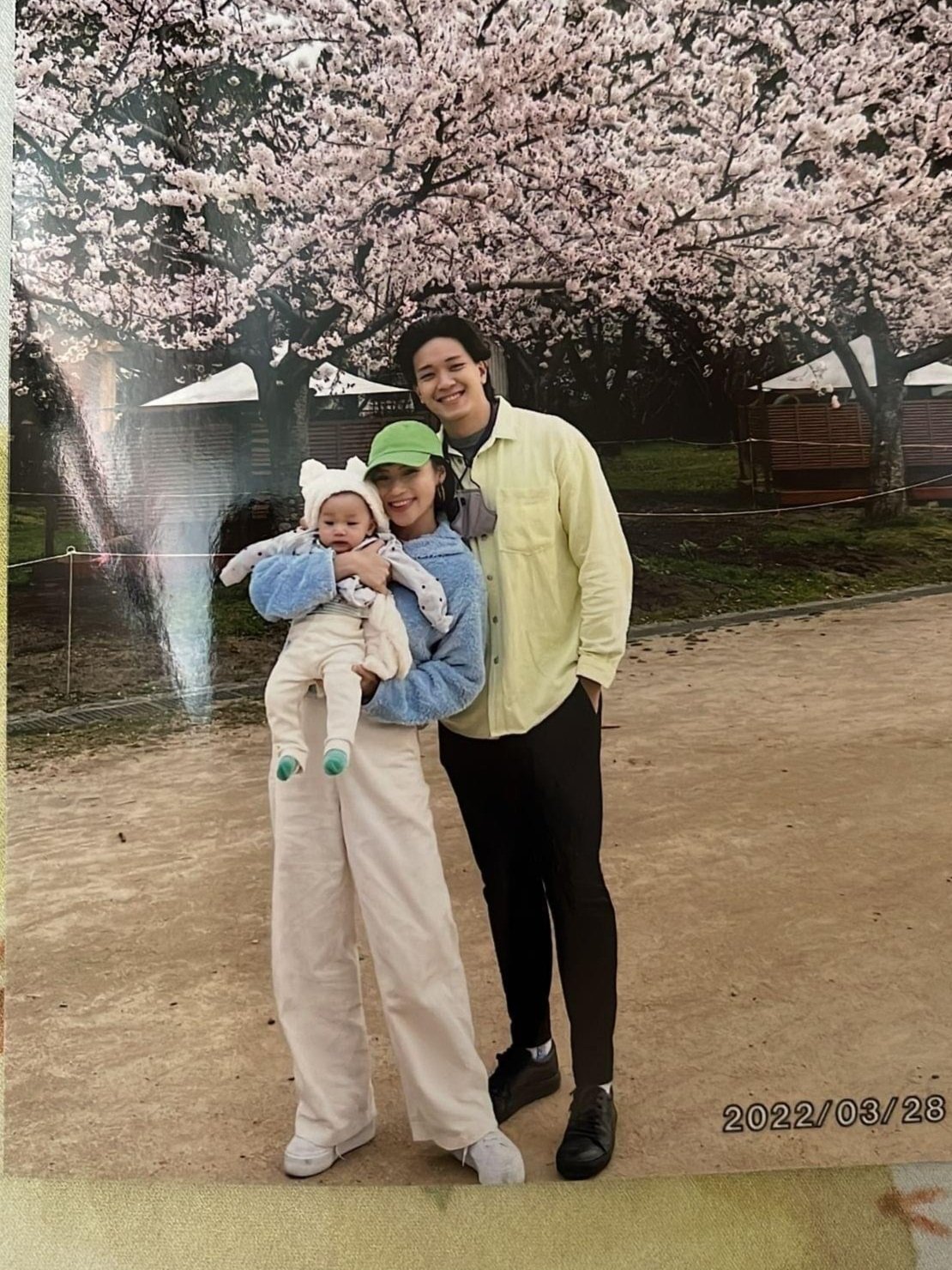

Here’s another thing I think matters: am I a good exemplification to my son? Am I shortchanging him of anything? Have I deprived him of resources? Do I really understand what he is going through?

The question is: Am I spending all my energies chasing after my business and status instead of being present, living in-the-moment, appreciating everything I have as a blessing rather a indicator of what I lack?

There’s this story about David Letterman, the host of the Late Show with David Letterman, who, after airing his programme for a record-length of thirty-three seasons, decided to walk-away from the show biz. At its peak, his programme was making $30 million a year and tuned in by millions worldwide. “I’m quitting. I’m retiring. I won’t be at work every day,” he told his young son, Harry. “My life is changing; our lives will change.” Expecting his son to question his rationale for leaving, Harry replied, “Will I still be able to watch the Cartoon Network?” “I think so,” Letterman replied, stifling his disbelief in silent demure, “let me check.”

The needs of our children are incredibly humbling. Simple, pure, easily fulfilled. We’re narcissistic to think that only what we do matters. That we’re so important. Then we run ahead, grinding for things that make up a speck of importance, telling ourselves that it’s for the benefit of our career, our kids, our well-being, their well-being.

There’s this voice in my ear that keeps going, memento mori.

Remember you will die.

And If I am dead, what use is this thing I’m constantly chasing after? And If I am dead, what's left for my family?

No family can thrive if its leaders—you, me—are in a continuous surge of pressure to perform. And no family can thrive if its leaders have misplaced priorities.

But we can turn it around. Not literally of course, but in a sense that knowing that someday everything will end, we can reorient our efforts on the things that will leave a lasting legacy.

Even after he had been delivered the devastating blow of pancreatic cancer, Steve Jobs roared back after his initial recovery with even more fire than before. The reality of death reminded him that he had nothing to lose. And though he eventually lost the battle against cancer, he forged ahead full speed with the remaining time, producing what many of his colleagues described as his best days with a revolution of the iPhone, iTunes and the iPad. And of course, with his family.

Better late than never.

I'm not here to tell you what should matter for you, but it's clear there's a misrepresentation of what's taking too much of our time and what needs more of it. Your acknowledgement that everything will end should trigger you to contemplate on the choices we make.

Those things you think doesn't matter, does.

Remember you are mortal.